Hydraulic Fracturing FAQs

Is fracking safe?

No, fracking, as currently practiced across the United States, poses serious risks to the health and safety of communities and the environment.

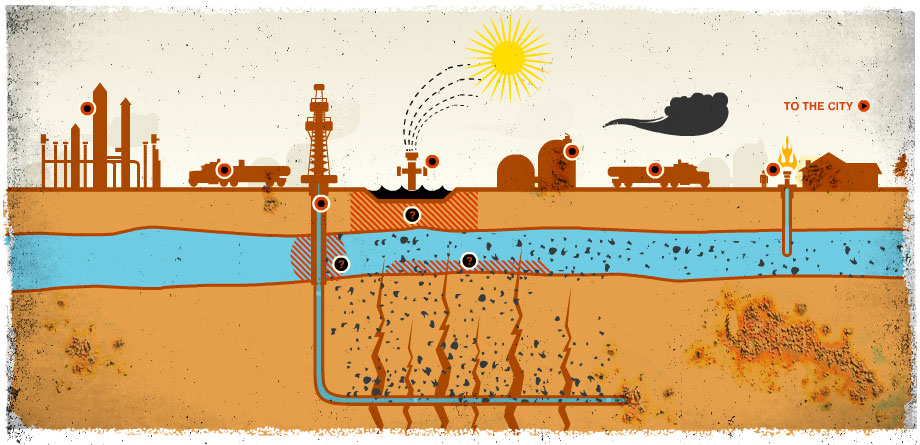

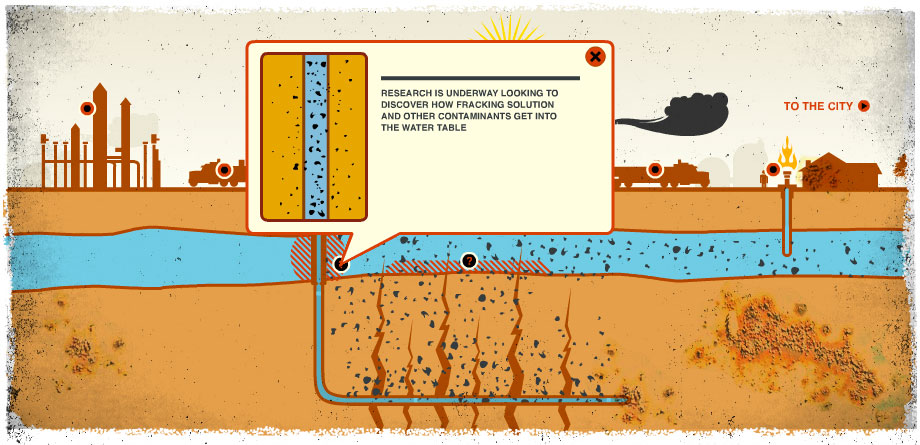

Water supplies across the country have been contaminated in fracking-related cases -- either by natural gas that migrates out of wells and into underground aquifers, or by any number of byproducts from of fracking process: chemicals, harmful and/or toxic substances from the underground rock such as naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORMs), dissolved solids, liquid hydrocarbons including benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene, and heavy metals.

How serious is water contamination due to fracking?

Very serious. For one thing, we don't even know all the chemicals being used for fracking. But many of the ones we do know about are well-documented (1,2,3) for causing cancer, birth defects, and disorders of the nervous system. The same is true of many naturally occuring but highly toxic substances that are unearthed in the process, then seap into the water supply.

What do you mean you don't know all the chemicals being used for fracking? Haven't you done your research?

Oh, we've done our research, alright. The reason many fracking chemicals go unknown is they're never actually disclosed at all, anywhere, to anyone, ever.

Fracking was explicitly made exempt from the Safe Water Drinking Act by a piece of energy legislation passed by Congress called the Energy Policy Act of 2005. This exemption allows drilling and fracking companies to inject unknown and/or toxic materials directly into, below, or adjacent to underground sources of drinking water without reporting the chemicals or the quantities of these chemicals to the government or to the public.

What are the environmental considerations of fracking?

While there are serious public health risks posed by fracking, there are major impacts on the climate, too. Methane, the same thing as natural gas, is a potent heat-trapping gas, up to 105 times more powerful than carbon dioxide upon release over a 20-year interval. Methane leaks at every stage of a fracking operation, from production and processing to transmission and distribution. The much-touted 50% reduction in climate impact from burning gas is not likely to be achieved for many decades -- if ever -- due to leaking. And we don't have many decades to stabilize the climate.

Don't we have the technology to make fracking safe?

Nope, no technology currently exists to make fracking safe. Here are some of the numbers from reports released by drilling giants Schlumberger, Archer Oil & Gas, Southwestern Energy, and the Society of Petroleum Engineers:

These industry reports support similar findings from state agencies, like the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission.

Some recent modifications to cementing regulations misguidedly include requirements on cement strength. But it is not a question of stronger cement or better technology. Industry's own documents say that:

"strength is not the major issue in oil well cementing under any circumstances … cement clearly cannot resist the shear that is the most common reason for oil well distortion and rupture during active production."

In other words, the high stresses and rock movements deep underground will cause a significant proportion of wells to fail no matter what.

How deep do natural gas wells go?

The average well is up to 8,000 feet deep. The depth of drinking water aquifers is about 1,000 feet. The problems typically stem from poor cement well casings that leak natural gas as well as fracking fluid into water wells.

Why do so many wells leak?

Pressures under the earth, temperature changes, ground movement from constructing nearby wells, and shrinkage crack and damage the thin layer of brittle cement that seals the wells. And getting the cement right as drilling goes horizontal is extremely challenging. Meanwhile, once the cement leaks, attempting to repair it thousands of feet underground is expensive and often unsuccessful. Even if successfully repaired, methane migration might have been occurring for months or years.

Some recent modifications to cementing regulations misguidedly include requirements on cement strength. But it is not a question of stronger cement or better technology. Industry's own documents say that:

"strength is not the major issue in oil well cementing under any circumstances … cement clearly cannot resist the shear that is the most common reason for oil well distortion and rupture during active production."

In other words, the high stresses and rock movements deep underground will cause a significant proportion of wells to fail no matter what.

Other industry documents show that well failure is a widespread problem around the world, that abandoned wells are a major migration pathway to aquifers, and that there are multiple scenarios by which gas and other contaminants can escape a well to contaminate water supplies.

Industry also asserts that the gas reservoirs they target are thousands of feet deeper than water supply aquifers. Therefore, industry says, there is no way the water supply could have been contaminated by their operations. But the cement barrier around the wells can fail from many causes, or be absent, allowing gas to migrate out of the well and into the drinking supply.

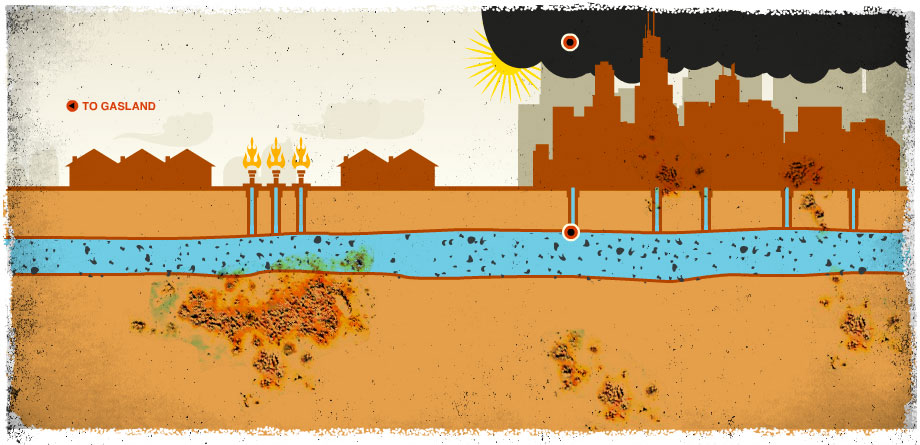

Are the flaming faucets from Dimock, PA fake?

Not only are the flaming faucets from Dimock real, but contamination has been conclusively traced to the fracking-related activity of one particular company.

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection's (DEP) investigation revealed that the methane contamination was due to gas drilling, specifically finding that 18 drinking-water wells in the area were affected by the operations of Cabot Oil & Gas (1, 2).

Further tests of Dimock water by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency talso clearly showed contaminants tracable to Cabot's fracking activities.

Industy arguments that methane occurs naturally in the environment in the Dimock area and therefore should be expected in the water suplly are dangerously misleading. A Duke University study found that drilling into the methane layer allows the natural but toxic gas to migrate into the water supply.

Haven't there been flaming faucets for years because methane is a naturally occurring gas?

The flaming faucets documented in Gasland are the product of natural gas migration into water supplies in most cases due to fracking right next door. Numerous investigations have confirmed this fact, including studies by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and many others. Industry is essentially claiming a giant conspiracy theory - that these families all across the country are lying in reporting that their wells never flamed before fracking.

Further, methane and natural gas are the same thing. So when industry claims methane in drinking water supplies is "naturally occurring" it's just another smokescreen. Industry also tries to defend itself by asserting that the gas found in water supplies sometimes has a different chemical fingerprint than the gas they are going after. They distinguish between biogenic gas - found closer to the surface - and thermogenic gas - found much deeper underground. Industry is after thermogenic gas because it's been "cooked" longer and therefore has a higher energy density. But industry's drilling pierces different gas layers and allows them to mix. Failure or absence of the cement well seal allows gas from any layer to migrate into the water supply.

Additionally, Duke University recently conducted a peer-reviewed study that links water contamination with nearby drilling and fracking, concluding that water wells near drilling and fracking operations were seventeen times more likely to contain elevated levels of methane.

Do you agree natural gas from fracking is a bridge fuel while we develop carbon-free sources of energy like wind and solar?

Fracked gas is a bridge to nowhere. Reports (1, 2) suggest fugitive emissions of methane are so substantial that they completely outweigh any climate benefits of gas as compared to coal. Further, the flood of cheap natural gas in the market is having unintended consequences for renewable energy, which is being further squeezed out of the market place.

Gas is already displacing renewable energy. The costs of wind and solar are coming down all the time but they are battling for parity with fossil fuels on an asymmetric playing field. Until fossil fuels have prices that reflect their true costs to society - via a carbon tax, for example - renewables will continue to face stiff odds. The glut of cheap gas is only making these odds stiffer.

Isn't gas better for then environment than coal?

The leakage of methane - a potent heat-trapping gas - likely outweighs much, if not all of the climate benefit of natural gas versus coal. When burned in a power plant, natural gas gives off about 50 percent of the carbon dioxide emissions as coal. But this ignores the widespread problem of leaking methane. Methane's warming potential far exceeds that of carbon dioxide: On a twenty year time scale, methane traps heat up to 105 times more effectively than an equal mass of CO2. Unburned methane is a byproduct at every stage of the gas development lifecycle, including production, processing, transmission, and distribution.

Multiple studies (1, 2) suggest that "fugitive emissions" of methane from wells and pipelines are significant, thereby offsetting the climate benefits of gas versus coal.

Indeed, gas produced from fracked wells may actually turn out to be worse than coal: Once fugitive methane emissions exceed 2-3 percent of total gas production, natural gas's climate advantage over coal disappears over a 20-year time horizon. Recent studies (1, 2) suggest leakage rates well above this threshold.

In addition, shale gas represents one of the largest reserves of carbon on earth. If we burn more than a tiny fraction of it, putting its carbon into the atmosphere, it will be impossible to keep global temperatures from rising beyond a livable threshold.

Won't fracking bring us energy independence?

No. The idea that fracking is the key to American energy independence is a myth. We don't use natural gas to power cars, and we don't use oil to generate electricity.

Also, much of the gas fracked in the U.S. might end up overseas. This reality is dictated by basic economics: gas will flow to the highest bidder. Currently, gas in Europe costs about 3 times more per unit than it does in the U.S. Prices in Asia are even higher. These realities are leading to an explosion of permitting requests for the construction of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminals on our coasts for the purpose of transporting gas overseas.

Once gas starts to flow overseas, moreover, it is only a matter of time before gas prices rise in the U.S. Eventually gas prices will be dictated by the world market - like oil - and no amount of domestic gas supply will be able to influence this reality. (Meanwhile the energy it takes to liquefy natural gas, and the additional leakage of methane during processing and transport of LNG, further erode any possible climate advantage).

What about the jobs created by fracking?

The jobs created by fracking are not the kind of quality jobs American workers deserve. They are dangerous, exposing workers to chemicals whose long-term impacts on human health are yet unknown. And there just aren't that many jobs to be had, especially when compared to the plentiful and sustainable jobs available in the renewable power and energy efficiency sectors.

Consider these statistics:

In contrast:

Josh Fox is currently conducting an investigation into worker safety and chemical risk. He has interviewed many workers who have been asked to clean drill sites, transport radioactive and carcinogenic chemicals, steam clean the inside of condensate tanks which contain harmful volatile organic compounds (VOCs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and other chemicals and have been told to do so with no safety equipment. Many workers have been harmed and made ill to the point to which they can no longer function normally and have been fired or quit without health insurance.

A bill to address worker safety, drafted by State Senator Tony Avella of New York, dubbed "CJ's Law" in honor of CJ Bevins, a rig worker killed by an unsafe site in New York State, currently has more than 30 co-sponsors and is moving through the NY State Senate.

Won't regulations force fracking be done safely?

Fracking is exempt or excluded from most major federal laws protecting environmental health. In the absence of federal oversight, states are empowered to regulate fracking. However, the current state-by-state patchwork of rules and regulations gives little cause for comfort.444

Fracking was formally exempted from the Safe Water Drinking Act by the Bush Administration in 2005 via the so-called Halliburton loophole - named after the company formerly led by Vice President Cheney that called for the exemption during Cheney's secret Energy Task Force meetings. Mirror exemptions exist under a host of other major federal regulations, including the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), the Comprehensive Environmental Response Conservation and Recovery Act (CERCLA), the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), the Superfund law, and the Toxic Release Inventory under the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA).

Isn't the Obama administration issuing new rules on fracking?

The new rules *only* apply to fracking on federal land, which is only a tiny slice of fracking nationwide. These rules are inadequate to protect federal lands and are currently being weakened by tremendous industry pressure. As stated above, there are no regulations which can make fracking safe, either on federal or private lands.

The Department of Interior announced proposed new rules to regulate fracking on federal lands. However, the vast majority of fracking in the United States takes place on private lands. Regulation of fracking thus almost completely falls to the states. But state regulations have hardly been able to keep up with the recent explosion of fracking activity, and the laws and rules on the books vary widely in stringency and enforcement. Studies have also documented how industry "captures" local governments.

There is also a considerable lack of transparency among companies involved in fracking, which is aided and abetted by state and federal regulators. For instance, while states like Texas, Wyoming and Pennsylvania require "disclosure" of the chemicals used in a fracking operation, the requirement is gutted by "trade secret" exemptions, which shield companies from disclosing their toxic recipes. The federal government also memorializes the trade secret exemption in its new proposed rules, which, again, are only applicable to federal lands. The federal rules include another major giveaway to industry, in that they would only require disclosure of the "disclosable" chemicals (i.e., those not falling under the trade secret exemption) *after* the fracking operation is completed. That leaves concerned citizens and watchdog groups powerless to monitor possible contamination of drinking water supplies in real time.

What about the University of Texas study that finds no connection between fracking and water contamination?

The University of Texas at Austin has withdrawn that study after an investigation revealed that the lead investigator, Charles "Chip" Groat, has financial interests in the natural gas industry, which he did not disclose in his report.(fn)Bloomberg News reported July 23, 2012 that Groat has been on the board of Plains Exploration & Production Co. (PXP) since 2007. As a board member, Groat receives 10,000 shares of restricted stock a year, as well as an annual fee, which was $58,500 in 2011 - according to company filings. Groat has since retired from his UT faculty position; Raymond Orbach, director of the Energy Institute at UT, which conducted the study, has resigned as well.3

What's in fracking fluid?

Fracking fluid is a toxic brew that consists of multiple chemicals. Industry can pick from a menu of up to 600 different kinds. Typically, 5 to 10 chemicals are used in a single frack job, but a well can be fracked multiple times, and each gas play consists of tens to hundreds of thousands of wells - driving up the number of chemicals ultimately used. Many fracking chemicals are protected from disclosure under trade secret exemptions. Studies of fracking waste have identified formaldehyde, acetic acids, and boric acids, among hundreds of others.(fn)

For each frack, 80-300 tons of chemicals may be used, selected from a menu of up to 600 *different* chemicals. Though the composition of most fracking chemicals remains protected from disclosure through various "trade secret" exemptions under state or federal law, scientists analyzing fracked fluid have identified volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene - all of which pose significant dangers to human health and welfare.

Industry says it's misleading to suggest 600+ chemicals are used in a fracking operation since only a small percentage of this number of chemicals is used per well. But this "one-well" model is the biggest misrepresentation of all: fracking operations in a gas play typically consist of many thousands of wells. Cumulative impacts are what matter.

How much water is used during fracking operations?

Generally, 2-8 million gallons of water may be used to frack a well. Some wells consume much more. A well may be fracked multiple times, with each frack increasing the chances of chemical leakage into the soil and local water sources.

The sheer volume of water brought to and from the fracking site means a glut of tanker trucks through your town. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation estimates each well, per frack, will require 2.4 to 7.8 million gallons of water. This translates into roughly 400 to 600 tanker truckloads of liquids to the well, and 200 to 300 tanker truckloads of liquid waste from the well. An eighteen-wheeler weighs up to 80,000 lbs. Day-in, day-out, these trucks destroy roads and bridges, leaving towns to clean up the mess.

Further, the one-well model is not an accurate representation of fracking operations, which can consist of 20 wells per "pad" and dozens of pads: Overall, 38,400 to 172,800 tanker truck trips are possible over a well pad life.

What happens to wastewater

Wastewater disposal is among the biggest challenges of fracking. Although up to 85 percent of fracking fluid remains underground, the wastewater that does return to the surface (also called "flowback water" or "produced water" or "brine") is contaminated and must be treated and disposed of. This liquid waste is frequently stored temporarily in open pits, or "misted" into the atmosphere. There are several options for permanent disposal of wastewater: (1) trucking to an industrial wastewater treatment facility; (2) trucking to injection wells deep underground; (3) reuse by recycling into another frack job. Each option has multiple environmental risks.

Can fracking cause earthquakes?

Fracking has been proven to cause earthquakes, directly and indirectly. The National Research Council settled the debate about indirect cause with a comprehensive study in 2012. The study concluded that the greatest risk of earthquakes does not come from drilling or fracking but from pumping the wastewater from fracking into deep rock reservoirs. Such wastewater injection was blamed for earthquakes that occurred in Youngstown, Ohio, on Christmas Eve and on New Year's Eve 2012, measuring 2.7 and 4.0 on the Richter scale, respectively. The British Columbia Oil and Gas Commission concluded that fracking itself directly caused seismicity in the Horn River shale play, and that those earthquakes damaged underground well structures.

Does fracking cause air polution?

Before the wastewater is trucked to a remote injection well or processing facility for disposal, wastewater ponds and condensate tanks release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) 24 hours a day, seven days a week. As the VOCs are evaporated and come into contact with diesel exhaust from trucks and generators at the well site, ground level ozone is produced. Ozone plumes can travel up to 250 miles. This is apart and distinct from the carbon pollution issue, by which methane and CO2 from the gas production and combustion process contribute to global warming.

What is horizontal hydraulic fracturing?

Horizontal hydrofracking is a means of tapping shale deposits containing natural gas that were previously inaccessible by conventional drilling. Vertical hydrofracking is used to extend the life of an existing well once its productivity starts to run out, sort of a last resort. Horizontal fracking differs in that it uses a mixture of 596 chemicals, many of them proprietary, and millions of gallons of water per frack. This water then becomes contaminated and must be cleaned and disposed of.

How does hydraulic fracturing work?

Hydraulic fracturing or fracking is a means of natural gas extraction employed in deep natural gas well drilling. Once a well is drilled, millions of gallons of water, sand and proprietary chemicals are injected, under high pressure, into a well. The pressure fractures the shale and props open fissures that enable natural gas to flow more freely out of the well.

What is the Halliburton Loophole?

In 2005, the Bush/ Cheney Energy Bill exempted natural gas drilling from the Safe Drinking Water Act. It exempts companies from disclosing the chemicals used during hydraulic fracturing. Essentially, the provision took the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) off the job. It is now commonly referred to as the Halliburton Loophole.

What is the FRAC Act?

The FRAC Act (Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness to Chemical Act) is a House bill intended to repeal the Halliburton Loophole and to require the natural gas industry to disclose the chemicals they use.